A Bird, A Homeland, A Mirror: How the Kōlea Found Me

A poetic research essay exploring the kōlea bird’s migration, its connection to Turkic origins, and how this informs Studio Kōlea’s art practice.

Photography by Rae Okawa

Some stories are not chosen, they recognize us.

This essay examines conceptual foundations behind my practice.

It is not a confession, but an articulation of the frameworks that inform my work.

I. Encounter: The Bird on My Shore

Every year, as the trade winds soften and heat deepens before autumn, a small, alert shorebird appears on the beach near my home in Hawai‘i.

At first, I noticed it as one might notice a recurring stranger — familiar, yet unexplained.

Later, I recognized it in children’s books and animated films, where it was shaped into delight rather than meaning.

But one day, a quiet internal instruction emerged:

“Research this bird.”

I did not know that this impulse would open an origin story.

II. Discovery: The Altai Connection

Kōlea Bird Illustration

What I found was not simply ornithological:

Pluvialis fulva, known in Hawai‘i as the kōlea,

migrates from sub-Arctic regions: Alaska, Eastern Siberia, and lands adjacent to the Altai Mountains.

Anthropologists describe Altai as a cultural cradle for Turkic civilizations, a region that echoes within the ancestry of my own heritage.

The bird I observed here, at the edge of the Pacific,

had flown from landscapes embedded in the memory of my people.

I thought I had chosen a symbol.

In truth, the symbol had already chosen me.

II. The Rare Black Sea Detour

Later, I learned that ornithologists occasionally document kōlea

along the Black Sea coast,

a vagrant individual caught off-course,

arriving where my familial roots lie.

Biology names this accidental migration.

Interpretation names it something else:

an axis between geography and psychology,

between instinct and inheritance.

IV. Migration as Metaphor

Studio Kōlea Logo Illustration and Design by Ezgi Iraz.

Migration is more than movement.

It is an ancient choreography of return,

a negotiation between longing and departure.

Diasporic individuals experience this similarly:

they orbit homelands that are lived in memory

as much as in terrain.

The kōlea became an external architecture

for an internal reality,

a mirror of belonging suspended between worlds.

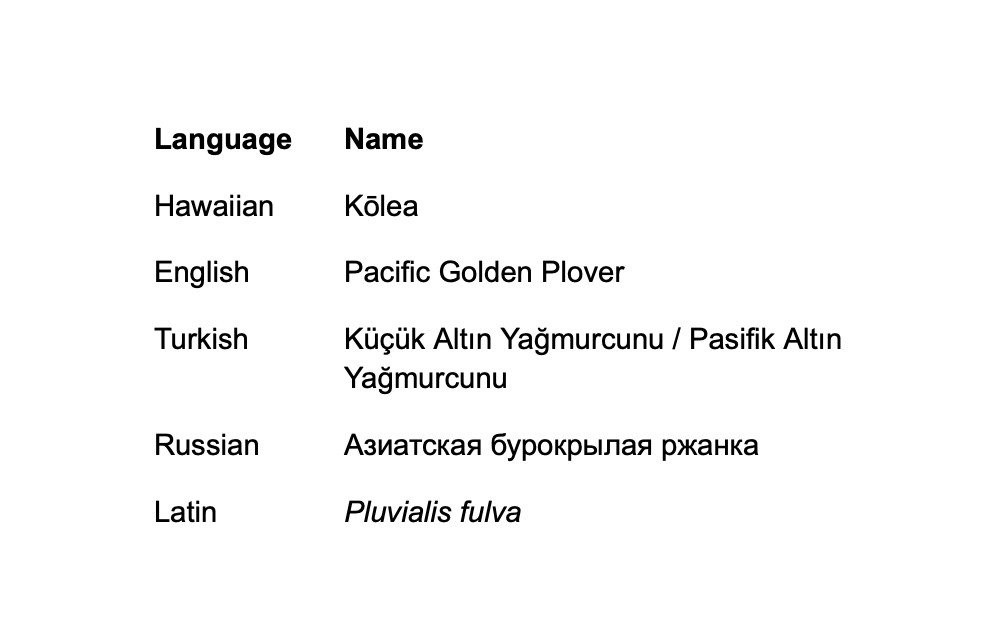

V. Names as Identity Frames

Across cultures, this bird holds multiple identities:

Names act as ontological gestures,

they define how a culture perceives and positions a being.

That this bird carries a Hawaiian name

in the place where I live,

yet embodies a Turkic environmental origin

felt like an encoded bridge between my worlds.

VI. Art as Cartography

Before I understood its migration,

I had begun painting interiors of rest,

women in mu‘umu‘u dresses reclining in transitional spaces,

soft rooms balanced between worlds,

cups borrowed from Istanbul tea tables

and placed into Hawaiian settings.

People called this fusion.

I called it instinct.

Only later did I recognize

that I was mapping what the kōlea already knew,

how culture migrates, how identity nests,

how belonging becomes visual form.

The bird had traced these routes

long before I arrived.

My art was not inventing the story

it was recording it.

VII. Rest as Hereditary Intelligence

The kōlea works with extraordinary endurance:

crossing oceans, raising young, navigating risk.

And yet, it pauses,

resting on lawns, shorelines, or coastal stones.

While human cultures often urge women

to sustain without ceasing,

the kōlea embodies a contrasting truth:

rest is not indulgence

it is biological wisdom.

My paintings of women at rest,

wrapped in mu‘umu‘u, suspended between movement and arrival,

are therefore not fantasies

they are instructions taken from the natural world.

VIII. Conclusion — This Is My Soul’s Work

Migration.

Collaboration.

Rest.

These are not unrelated concepts,

they form a cycle, a praxis, a narrative.

Studio Kōlea exists because a bird

documented this connection

long before I could paint it or speak it.

This is my soul’s work.

Written by: Ezgi Iraz